Every time I see a typewriter, something in me shifts. Nothing dramatic. Just enough to make the room feel off-balance.

I own three typewriters. Two of them work. The third, my Royal Remington, came to me broken. Carriage string snapped. Bought it that way. I told myself I’d fix it. I haven’t. Sometimes I take it apart, poke around its insides like I might accidentally learn something, then leave it the same. Or slightly worse. Mostly, it gives me something to mess with when my brain starts pacing.

It’s heavy enough to kill a man, probably. I keep it where I can see it, like that changes anything.

The first Remington I ever touched wasn’t mine.

I was seventeen and radicalized, but mostly just socially weird. I didn’t know how to be around people, so I leaned on one-liners and borrowed ideology. I had a copy of The Communist Manifesto in my backpack and no real understanding of it, just strong opinions and a red Sharpie.

I sat in the back of class making half-jokes and hoping they sounded like conviction. I was just loud enough to be annoying, not remembered.

So when my English class took a field trip to the Hemingway Museum, I wasn’t expecting enlightenment. I just wanted to get through the day without being perceived too much. I kept quiet. I took mental notes. I judged the wallpaper. The house smelled like curated sadness and mildew. The tour guide talked about Hemingway’s first story like it had been carved into stone tablets. We nodded. We pretended to care.

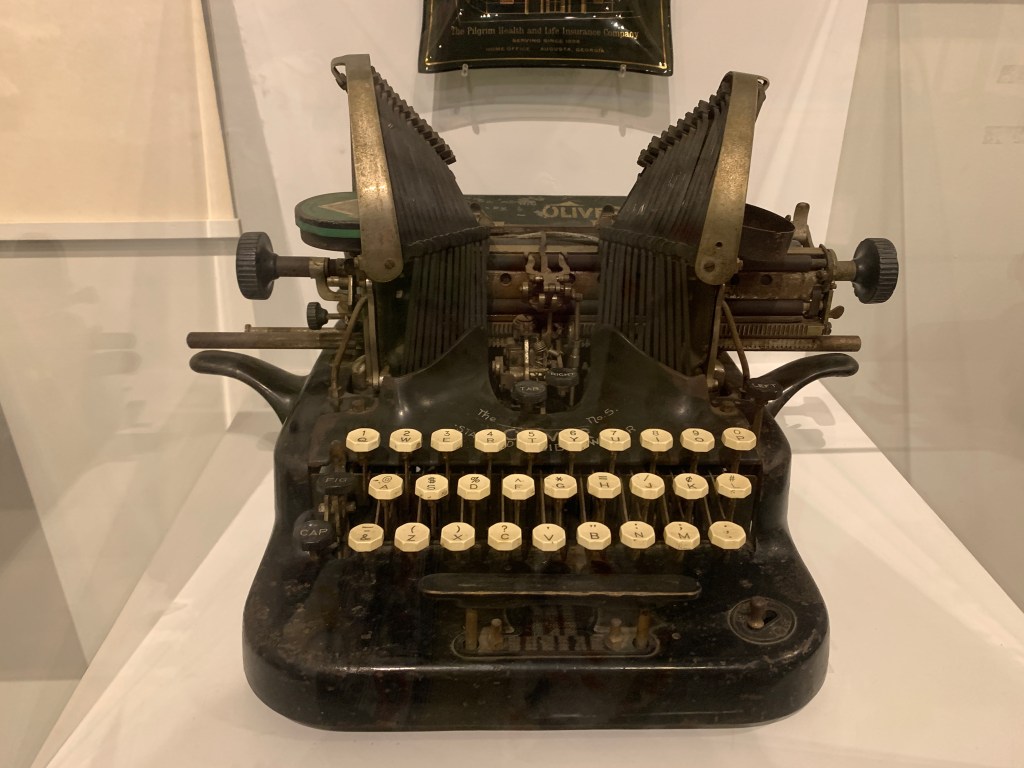

Then I saw the typewriter. On Hemingway’s desk. Guarded by velvet rope like it might still be contagious. I waited until no one was looking and typed something I’d read in a zine once: PROPERTY IS THEFT. It felt important. And stupid. Probably both. Something dumb to prove I was there.

I was still standing there when the room changed.

The adults disappeared. I don’t mean metaphorically. They were just gone. We stood around like we’d been left behind after the Rapture. The room got weird. Heavy. Like something was crawling underneath the floorboards of the day.

We found them outside. The sky looked too normal.

Mr. Miller was on the curb, folded into himself like someone trying not to spill. His phone was in his hands. His Soundgarden shirt peeked out from under his dress shirt like a quiet scream.

His mouth kept moving like he was rehearsing how to say the world ended without scaring us.

A chaperone sat beside him with one hand on his back and the other gripping a coffee cup too tightly. No one was talking. Just breathing in the shape of talking.

“There’s been a shooting,” someone finally said. Not here. Somewhere nearby. A college. A name we recognized. Dead.

No one moved. No one said the right thing. We just stood there, waiting for an adult to explain how we were supposed to react.

I remember staring at a chaperone’s untied shoelace and thinking, that feels about right. I wanted to make a joke. Say something dumb. Just to prove I could still talk. But everything felt too loud, even the quiet. Mr. Miller looked like a man who had run out of ways to pretend things were fine.

They told us to go back inside. So we did.

There was nothing else to do.

Grief has no designated chaperone.

I walked back through Hemingway’s house like I was tiptoeing around something freshly dead. The furniture looked staged. The letters behind glass felt like warnings. My hands stayed in my pockets, knuckles tight, like I was holding something I didn’t want to drop. My reflection in one of the cases looked unfamiliar. Not sad. Just emptied out. No one touched anything. No one spoke. We just moved through the house like we were temporary.

Now I look at my Royal Remington and think about that day. Still broken. Still sitting there like it’s waiting for me to fix something I never knew how to fix. I think about what I typed on Hemingway’s typewriter. Still caught in the ribbon, probably. Still trying to mean something.

Sometimes I think I take apart the Remington because I never said anything that day. Because I didn’t know how to speak when it mattered. Because silence feels like something I picked up and forgot to put down.

It was the first time I realized an adult could be just as broken as us. And that maybe no one’s built to hold any of it.

But mostly, I think about Mr. Miller. The way his shoulders folded. The way the world shrank around him. The way we all stood there, afraid to move, like something might break if we did.

How the world went quiet. And how I haven’t trusted the sound of it since.

***

Mallory Smart is a Chicago-based writer and the Editor-in-Chief of Maudlin House, an indie press for the weird and restless. She hosts the literary and music podcast Textual Healing and the horror movie podcast That Horrorcast. Her latest book, I Keep My Visions To Myself, is out now from With an X Books.

Twitter: @malsmart

Website: mallorysmart.com

image: MM Kaufman